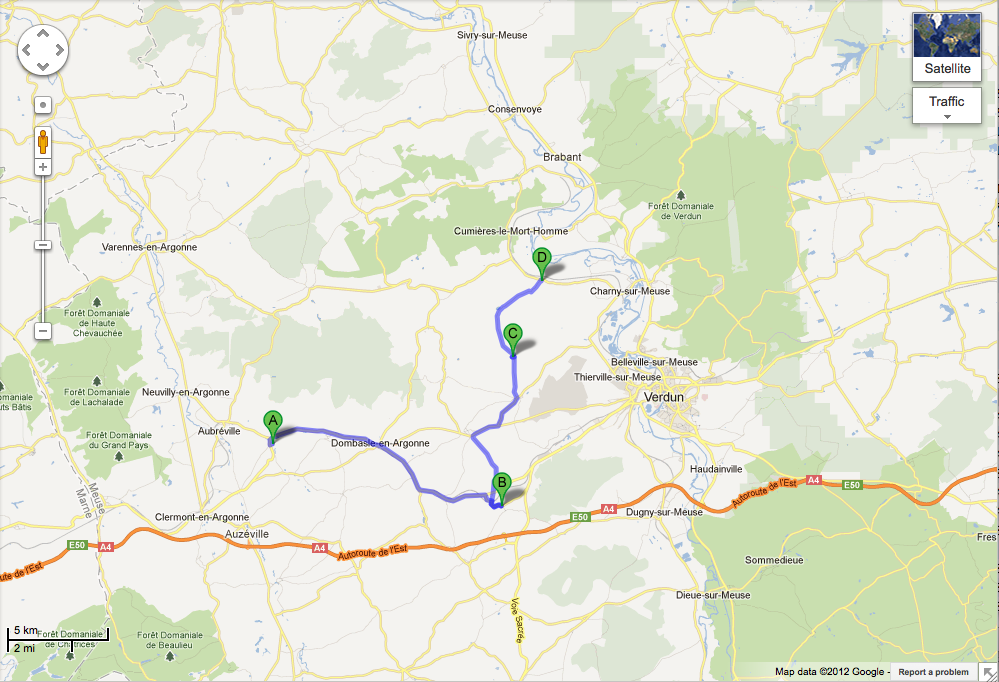

[left Liverpool 6-24, train 6-25, Bordon 6-26, leave Le Havre 6-29, Bain-de-Bretagne 6-30]

1.

Liverpool about which I had heard so much! Could it be possible that our dreams could finally have been realized. At last on European Soil. Could I have believed one who would have told me that I would be in Europe at this time. Nothing but the call of war could have done it. Now the pages of English History and all that surrounded in my memory began to flit through my mind. Later however when I had occasion to visit the Islands for as many as four months I had a greater occasion to recall and learn, as well many novel happenings of interest in the beautiful Islands.

The reception of the inhabitants of the city was very pleasing.

2.

After we had said adieu to the Leicestershire , we were ordered to use of emergency rations which we had carried with us from Camp Mills. The people stood about seeing what sort of people we were. I discover that many English people still think that the majority of the Americans are Indians and equal in kind to the Hottentots of South Africa. Perhaps many were watching us through curiosity to learn what sort of people we were. After eating our lunch we marched through the city, cheered with the best ovation. The inhabitants were very glad to see us, especially those who had sons and husbands in the war.

I thot we never would arrive at the depot. We were all very tired after our sea journey. However the shouts and cheers

3

and welcome of the Liverpool inhabitants tended to drive all these languid feelings to the rear, and make us feel gayer. The people would shout from the windows as we passed. Pedestrians on the streets would half and take notice of us, and of course we being soldiers were particularly anxious for everybody to see us. The boys would always take note of every pretty girl seen.

Each step brot us nearer the station. As we entered a British Band played for us. When we arrived there the trains were already waiting for us. Thanks to the splendid arrangements made beforehand. Before we aboarded the train we were each given a slip of paper containing the welcome of King George to Americans troops. We appreciated

4.

that.

A few weeks after this an American paper came to my notice which told of King George reviewing the troops of the 324th Field Artillery. Fully an half column was devoted to this report in the American paper. King George was not there, but he welcomed us, just the same.

We left Liverpool the afternoon of June 24th. Our train was not crowded and I can say that our entire journey through England to Camp Bordon was a pleasant one. Arriving in June as we did the whole country was awakening from its dormant state of winter. The days were long and I watched the country scenery until nine o’clock infact as long as

5

it remained light. The cattle were pasturing in the field. The sheep likewise were feeding on the grass. Occasionally we would see lovers making love by the railro near the railroad. The hills were beautiful. The chalk cliff

As we entered southern England the chalk cliffs began to appear. Occasionally a sharp, shrill whistle of the Engine would signal that we would quickly dash into a tunnel, and there are many tunnels on this southern journey.

Here and there would be a lowly thatched cottage. Row after row of brick houses of the same structure could be seen. These continuous chain of similar swellings approached monotony of vision sometimes, but the surrounding views of landscape tended to lessen this little discrepancy of

6.

beauty. Each square foot of land seemed to have been touched by the hoe of the farmer. I thot to my self and wondered if America would sometime be so hard pressed to land that she would gave to utilize all the steep hillsides, and certainly that time, will speedily come. All this land along my trip had been touched by the hand of man—not that ruggedness of nature which we have in some parts of America.

We all enjoyed this trip. One would remark to the other: “That scene is beautiful.” Now and then someone would allude to our future in France or wherever we were going. No body know. “Tut, tut!” said I “Let us enjoy the present and not think of what the next few months has in store for us.

7

That we generally did.

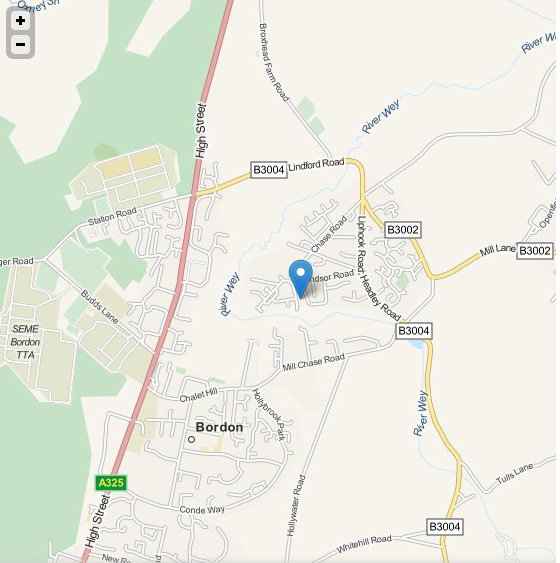

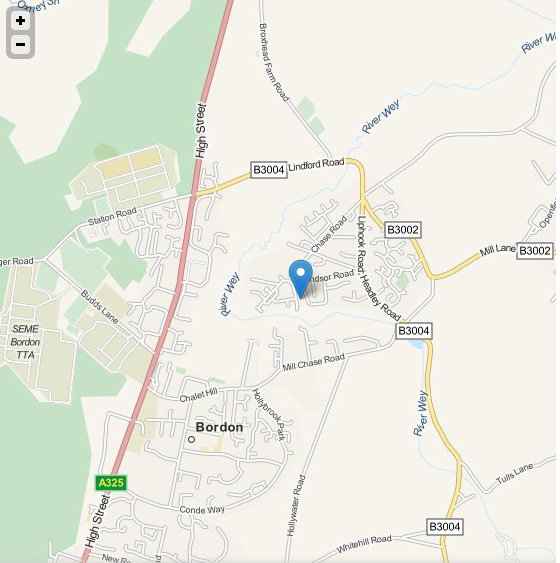

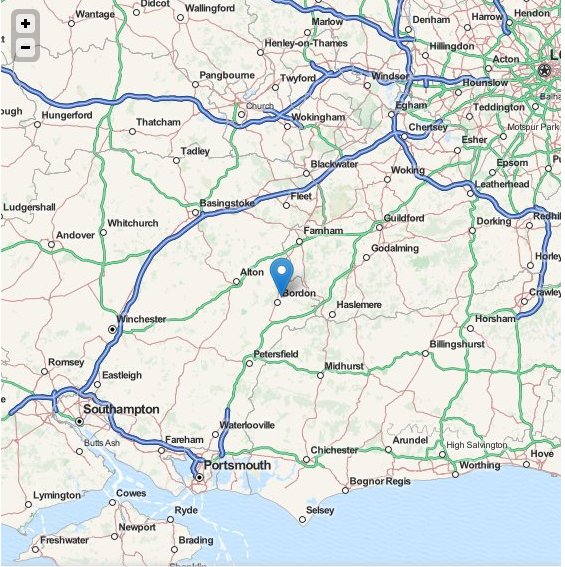

About three o’clock a.m. June 25, someone shouted “Jump off.” With this command all awakened, slung our packs on our back, ready for another hike to somewhere. We seemed to have landed at the end of things, but with a little time to make ready the officer who had come to meet us, marched us through the entrance to Camp Borden. This camp is about 25 miles N.E. of Southampton. We seemed to have gone there to await transportation across the channel.

We passed some very nice barracks, hoping that some spacious rooms were awaiting us with comfortable cots. A few minutes saw us out of sight of these barracks in an open field

8

My pal said “Guess we’re going to have to pitch our pup tents tonight.” And I agreed with him. However as we proceeded farther we saw the squad tents ahead. It was getting daylight by now.

Having been assigned to our tents, as many as could possibly sleep in them, we had an early breakfast which had been prepared by English soldiers—principally those who had seen the realities of was and had been disable through wounds and natural causes. We had some good ham at this place. In fact during all the time spent here we had plenty to eat.

Each of us availed ourselves of cleaning up here. There were shower baths and we truly needed a bath after travelling so much by train. Of course

9

we had bathing facilities on the ship, but the water was salty which made the use of soap next to impossible, so the baths there were not satisfactory.

This was a lonesome place. A small town lay near the camp, which gave one all the more a lonesome feeling. The Y.M.C.A. afforded us a place to drop a line to those we had left behind over the sea.

We had but a short time to remain in this camp. The noon of June 26th found us on the march for our train to Southampton. We were not sad to leave this camp. It was so situated that everything about seemed dead or dying. We were in the Southern metropolis in a short time.

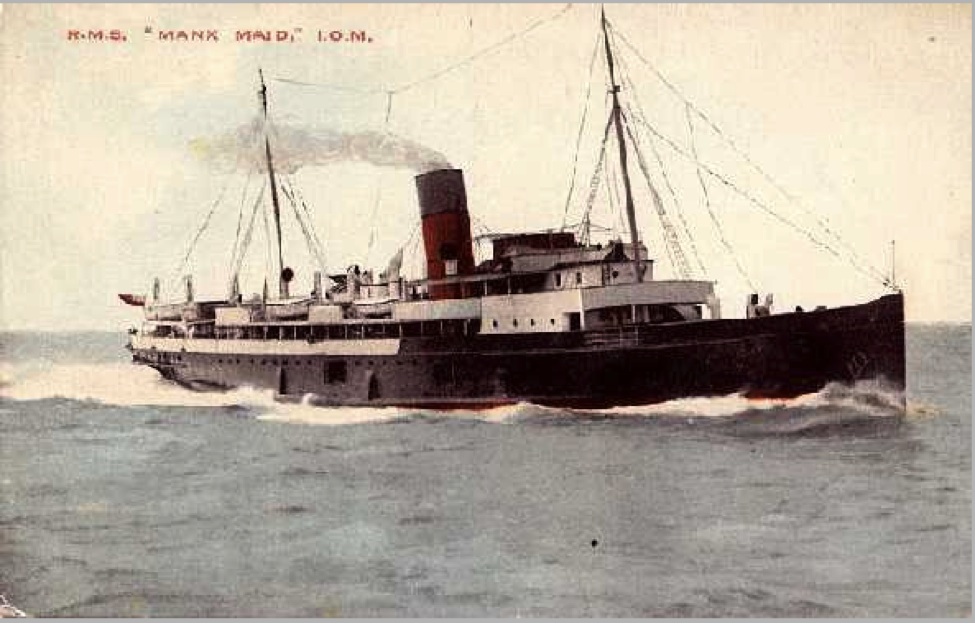

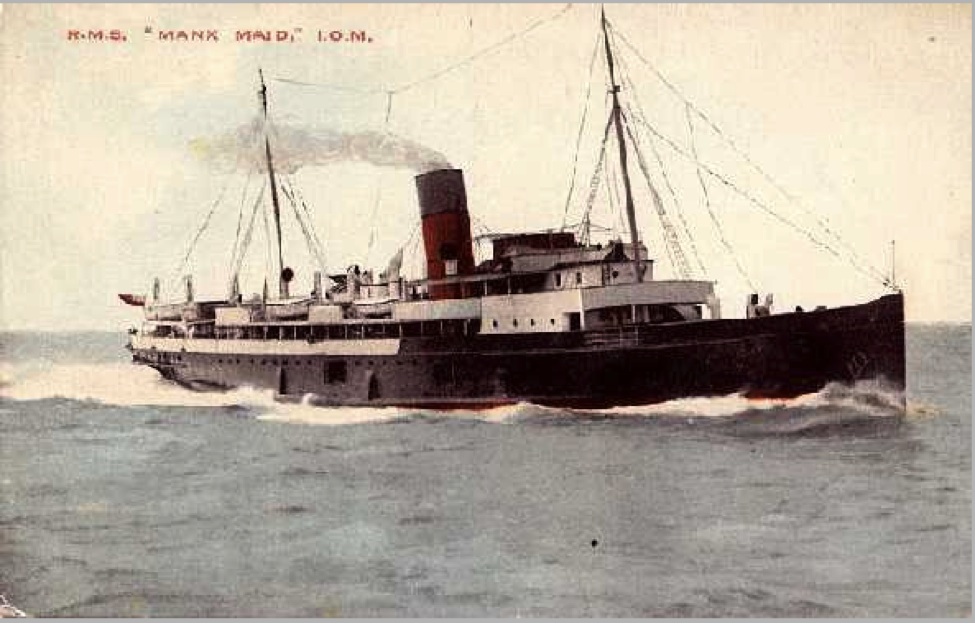

And now for the boat

10

ride over the Channel. We remained in the city until eight p.m. that evening. The boat was small. We thought we were crowed [sic] on our journey across the Atlantic, but that had nothing on the travel over the Channel.

Everyone aimed to sleep but I’ll venture to say but few made a success of their attempt. I never saw such a pile of humanity as there was about midnight on the floor. I awoke and cast my eyes about, and with a little scrambling I [unreadable] to raise my head enough to look over the tired bunch of Ohians. Sardines were never canned closer.

Occasionally I would awake and someone would be on top of me. The one on top could rest fairly comfortable. I had thot something of remaining on deck and sleeping, but the air was

11.

too cold, and it was either go below or become very cold, so I chose the former.

A sea plane circled about and followed us for some distance from Southampton. We keep up our zigzag mode of travelling, but at that we were sighting land the morning of June 27. Now we were out of all danger of submarines. Not a man in all our group had been lost thus far.

Now we were ready to visit Le Havre. Here we experienced our first insight into French life. Now we were about to utilize what French we already knew. You know we had school in Americans camps, and there many had studied French. At least most all knew how to say Bon jour, Mademsoiselle, and

12

that was enough for some of them. They would usually volunteer to say the remainder.

As we marched along the street the Kiddies would come from the allies and ask us with some mixed languages, “Avec vous, biscuit? Avec vous penny”? The hawkers on the street would follow us and try to sell oranges and chocolate. They had learned from previous Americans troops that we dearly loved our chocolate. The prices were steep, but we wanted such eats and we purchased them.

We marched and marched. Passed though the city. The streets were so narrow in places that when we marched in squad formation they would be full. Up a long hill we went, passing through the residential section of the city, until we came to

13

opening to a temporary military camp. There we were introduced to our first military

Here again we had the pu squad tents, and about eight to ten men were placed in each of these. Circular boards Here I had the best bath ever, One of those kind where they close you in a very hot rom until you perspire and produce your own bath through your own sweat. After taking the sweat bath we were admitted to the cold shower and we certainly felt clean when we went though such a thorough cleaning process.

Entirely surrounding this camp was a barb wire fence about ten feet high. We all very much desired to visit the city o pass, but no permits were given. This was real prison life and we

14

were treated as such. Guards were placed about all the exits and they halted many of the men who tried to escape unnoticed. Many did escape through [the word ‘search’ is above the space here] passage ways through the fence. I suppose that some troops had preceded us that did not act becoming of gentlemen, and as very often occurs, especially in the army troops are judged according to their predecessors. Anyhow we were penned with little to amuse ourselves.

Women about this fence would try when the guards were not watching slip bottles of wine thru the fence to the boys. The wine was nothing more then watered apple cider, but the boys bit and paid as high as a dollar a bottle for the stuff. These women

15

were principally Belgian refugees who had come from the occupied territory to evade the outrages of the Germans.

As luck would have it we were not in this camp very long. We left Le Havre about noon June 29 for somewhere in France.

We were very much surprised to see the mode of conveyance they had waiting for us at the Le Havre depot. We immediately up arrival at the depot looked about for passenger coaches, but to our own sad disappointment we were ordered to aboard box cars, with 38 to 40 men to the car. French box cars are not much more than half as large as the ordinary cars in America. These cars

16.

were marked in this manner—“40 hommes’

8 Chevans, which meant forty men or 8 horses. We lived similar to horses on that trip too. We did not have room to lie down. Some sat on boxes during the night, and those who tried to sleep, did so very uncomfortably. In fact we went to sleep in quarters. First one leg, then an arm etc. We were lying on top on one another and why shouldn’t we go to sleep in parts?

There was usually one square (or partly square) wheel on each box car, and bumpity bumpity we would jog along.

Again we did not know where we were going, and I have heard later that our commanders did not know.

17

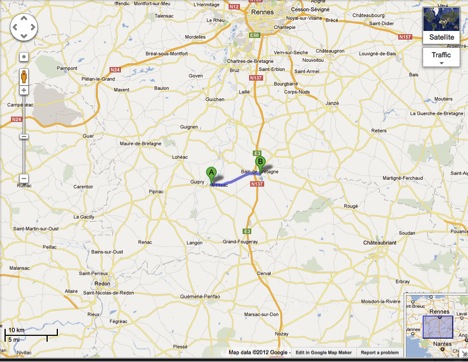

I had a map and had carefully traced our route and by examining the box cars I saw that they were billed to Messac. You know they usually bill box cars to certain town and that destination is found on the bill.

We would see other troops on the way and inquire of them if they know for where we were bound. They could not inform. Those of us who could speak a little French would try and converse with French [there is a suffix on ‘French but I cannot make it out] along the route, but usually they could give us little satisfaction. We were a dissatisfied lot at the time.

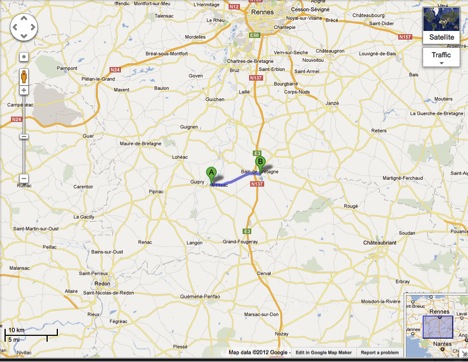

Luckily again, we were not to remain for a long time on this train. We arrived at a small town by the name of Messac

18.

in Old Brittany, and since our car was billed there we though that we had reach our destination, but no. We were to proceed to another town. I have heard later that we were travelling on another regiment’s order.

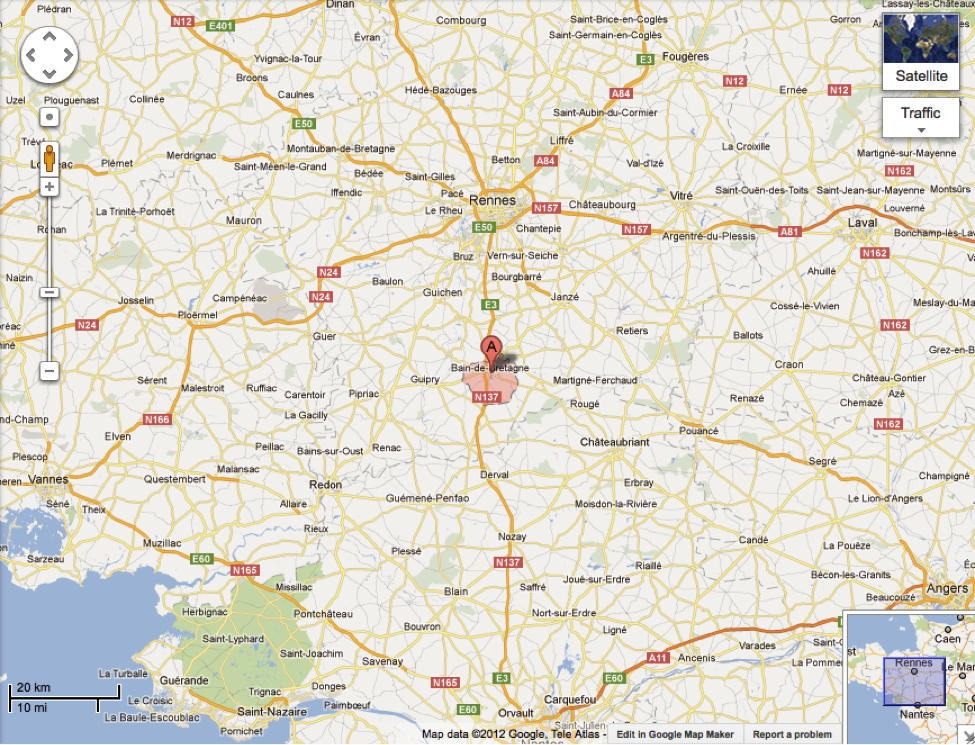

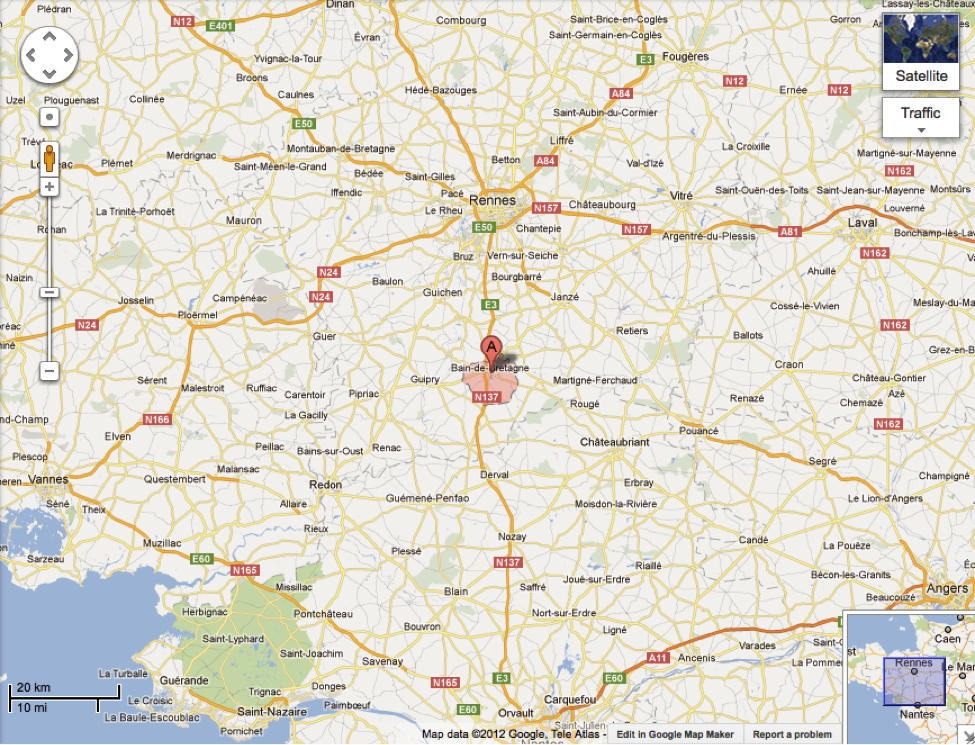

We arrived at Bain de Bretagne the evening of June 30. It was Sunday evening and the people of that village all turned out to welcome us. The ladies all had on their Sunday clothes and we thought we were coming to a very agreeable locality, and I can’t say that we didn’t.

[note Guer just to the west.]

[note Guer just to the west.]