1

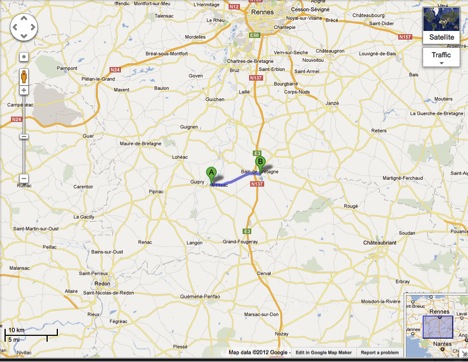

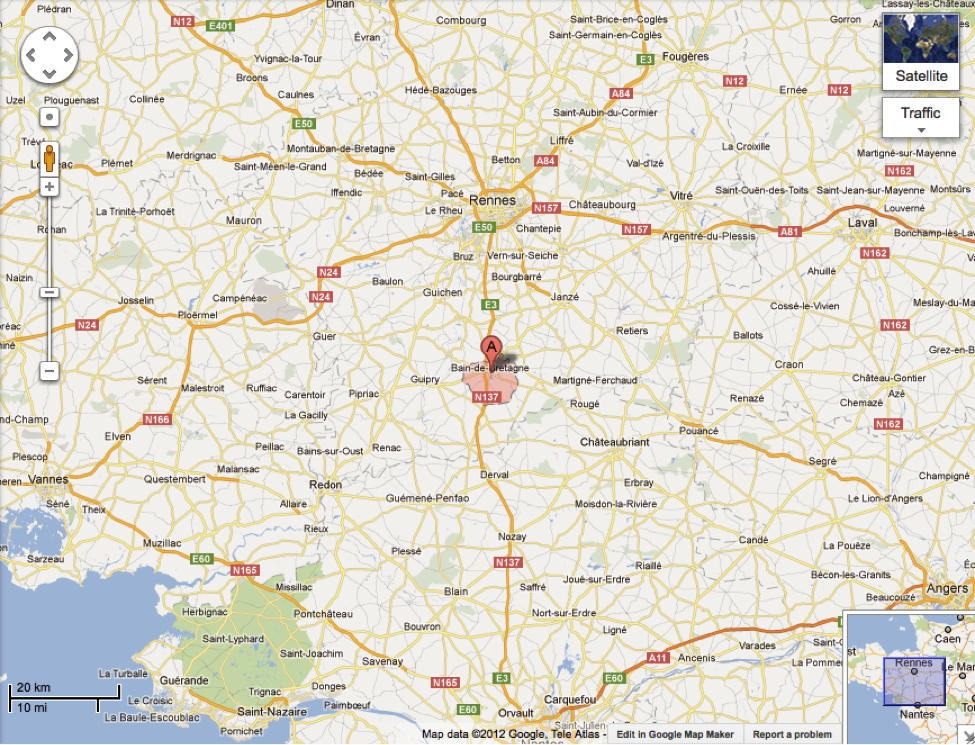

Bain de Bretagne

We arrived at the Bain of Brittany July 30, about four in the afternoon. The inhabitants were donned in their Sunday clothes and had the appearance of funeral attenders, since practically all wore clothes of black. These inhabitants were quite pleased to see us, and no doubt they, too, had expected to see kakki clothed lads with feathers sticking from their hats but we were quite a different lot from that. We more than likely resembled negroes, because of our very black appearance from riding so far in a box car with little opportunity to wash.

We were glad indeed to strike the privilege of washing that Sunday evening. There were

4

in an apple orchard near the house. Others sought shelter in the hay mow, while the remainder lived in the upper part of the house which was only partially occupied by French peasants.

The first few nights there I slept on the floor. Knowing that undoubtedly we would remain near Bain de Bretagne for several weeks, I began to look about for some straw to fill my tick. I purchased this from the tenant of the land, and after that I had a very comfortable bed for sleeping. The remainder of the boys did the same thing.

A true soldier very soon learns that he must take car of himself, as well as he can. Time and again one was thrown under conditions that was dis-

5

couraging,–and nobody about to tell you how to care for yourself. One must act on his own initiative if he does not suffer, and I usually found that through perseverance some thing could be found to make one more comfortable. If one were to trust to the gods to care for him in the army he would be a corps ere a month of actual service. One thing I have learned: and that is that one can live without any of the present day comforts and luxuries. One needs only to join an active army to discover how little he needs for existence in this world. It is true, however that such a life carries one back to many aspects of savage life.

So we arrived in this town of about two thousand in hab-

6.

itants in the midsummer months. Twas warm the day we arrived, but usually the weather was not too warm. The climate here was very agreeable. It was a very fine climate in which to drill and train troops,–neither to hot nor too cold—Just a comfortable even temperature. Many of the lads preferred sleeping in their pup tents, thinking that it would be preferable there. Luckily we had but little rain during our stay here.

We had only been here in our new French home five days until the time came when we would have to celebrate the Fourth of July. The French folk knew that American soldiers would not care to have this memorable day pass without some sort of celebration, so they in their very hospitable manner made preparations for a Fourth of July celebration. We, of course

7.

helped in whatever way possible. We formed inline and passed in review through the main streets of the city. This celebration was quite seasonal since it gave the “Mairie” an opportunity to welcome us as guests of his little city. The Mairie or mayor invited the officers to supper that evening and gave an address of welcome followed by a response by our colonel. Thus our regiment held their celebration in a foreign land. Take an American wherever you will he never forgets the meaning of the Fourth of July. He must celebrate.

[several lines blank]

8.

The inhabitants of Bretanny were very sociable. We had the opportunity of becoming acquainted with the habits and customs of the people in this community, since we were their visitors for several weeks. They were not long in learning what we want to but most. Soon orders were sent by the shop keepers for chocolate, candy of various sorts. One store purchased a number of articles of clothing which every soldier needed.

There were a countless number of little wine shops. I often thot that I would count the number of shops that dealt in drinks before leaving this village. I make a guess that 30. To an American who was reared in a dry section of the United States this custom was very odd. One could not enter a home unless the host of hostess would bring a

9.

glass of wine. This was done to show hospitality. A glass of wine means “you are welcome.”

I remember that a friend and I used to take walks through the country when we had nothing else to do, and as we passed the farm houses we would tarry and converse with the people. Five minutes would scarcely pass until the peasant would go to his cellar and bring a pitcher of wine for his visitors. The toast “Vive la France and Vive La America would always be given as the glasses sounded together. One had to partake occasionally of the entertainers would stare in awe, at your appearing unfriendly acceptance.

These people could not understand why we should be

10

be such lovers of water. They drank wine. Water was no good for them. The peasant when be went to the fields to work would throw his canteen over his shoulder, filled with wine. The wine commonly used by these poorer classes of people way nothing more than apple cider and very poor quality at that.

These peasants lived in a very peculiar fashion. A floor in their kitchen was an exception. They sometimes are and slept in the same room. There was nothing costly to be seen in the way of costly furniture. Surely such a condition is the only subsequent of their meager pay. They only received about three francs for a days work, which is only about sixty cents in our money.

11.

These people seemed to prefer living in groups. Sometimes in my walks thru the country I would see four to six houses in the country, all built in a cluster. The most of these houses were very old—some had stood the weather several hundred years. One would mostly see old people around these small clusters of houses. Perhaps a few children and their mothers. The men were either dead or at the front, but those who were left at home were still plodding away to keep those at the front as comfortable as possible.

Now and then one would see a Chateau owned by someone more fortunate insofar as wealth goes. Everything about such a home would be clean and uptodate in every way[.]

12

I remember one in particular which faced out little city. It was a beautiful home—surrounded by a forest. In the large yard flowers were planted about the house. The placed [sic] had enough quaintness about it to make one wish to tarry for a moment and which that he could converse more freely in their native tongue. The occupants of such home are usually intelligent and know well the history of their surrounding country. Occasionally I found someone who knew English very well and by the process of questioning and at the same time giving him a little information I could discover a number of things of historic interest about the place.

One of the best customs which the former inhabitants

13.

of this section of the country had was that of setting out trees along the roadside. Every lane in and about the small towns in this section of Britanny [sic] was finely decorated with trees on either side. These lanes would wind in and around to the houses in the country. These byways were very narrow and here and there the top of the trees would meet and form archways over the road.

There were no wire not rail fences here. The fences are very odd to an American[.] Heaps of dirt follow these by ways on both sides, and too this sort of fence would separate the fields. They were practically worthless and occupied considerable space, which might have been cultivated instead[.]

14.

We have an expression in English Ugly as a mud fence. Perhaps the derivation such an expression has its origin from these mud fences which are so prevalent in and about Bain de Bretagne. The fences served as places for wild blackberries to grow and when I first saw the fruit I supposed that these people were very fond of berries, but to my surprise they never touched there [sic] blackberries but let them waste and wondered how we relished them so. We told them we knew what was good.

On the average these people did not have too much to eat. Their main food seemed to be bread, butter and wine. Of course among those who had more money, a differ-

15.

ent condition existed. One evening I decided that we should have a surprise on one the my corporal friends. I proposed that we take the Corporal to dinner that evening under the pretense that we were only going to have a little drink of some sort. That evening we had an eight course dinner. I have never seen a better dinner but before man in my life. The cook was just late from Paris and she possessed all the characteristics of a French cook, believe me. In only give this show that some of the people in the community had plenty to ear, and we could get it if we paid well for it. The 324th F.A. left that town much richer than they found it.

16

Just below the town was a small lake, which nature had put there , and I suppose this was the origin of the towns name, since the Bain In French means bath. No doubt the inhabitants used to bath in this lake. Perhaps people would come from a distance to bathe in its waters, but now it is filled with groz [sp?], and the bottom is so muddy that one was dirtier when he came out than when he entered. We were ordered to bathe in this little lake at first, but later a much better place was found about one and a half miles distant. There the clear waters of the river Senucon [?] flowed. It was a very small river but the water was very clear and altogether acceptable for a plunge.

[next page?]

[Ille-et-Vilaine: Teillay, Ercé-en-Lamée, Lalleu, Tresbœuf, La Bosse-de-Bretagne, Bain-de-Bretagne, Pancé, Pléchâtel, Poligné, Bourg-des-Comptes—municipalities along Semnon]

[pages missing]

20.

in the fields. I was much surprised to see how these women worked both in the house and in the fields. They did more work than the men. Perhaps that accounts for their small living quarters. Such a woman would not have the time to care for more than a room or two.

The barns were oftentimes built in with the house. The chickens and cow lived in the same building with the people. Only a partition separated them. The people are not sanitary in our American way. The first thing that our boys did where we occupied the town was to clean it up. Brooms were put on the streets and the barnyards cleaned up. Much of this filthiness undoubtedly was due to the war

21.

The people were apparently to much occupied in other things.

We had remained here for five weeks. Miniature battlefields had been set up and practice on. Scouting parties had roamed the country for miles around. Some of the neighboring meadows were worn from the constant drill of the men.

We had become strongly attached to the people of Bain and they hated to see us leave. We have given them a liberal sum of money to maintain the orpans [sic] of their town. Some of the boys had fell in love with the boys of the town [well, I think CMC lost the thread of his sentence, but I could be wrong]. All things considered it was not an easy matter to leave the town. We had somehow become attached to the place, but we were not to remain here long. It was

22.

really only and [sic] accident that we were here. We were only waiting until a vacancy could be made for still further training in Camp Coetquidan.

We left Bain Aug. 15th with an ever standing invitation from its inhabitants to visit them whenever we could and later while we were in Germany [inserted above—‘During the Watch On The Rhine’] some of our boys returned to see the old friend whom they had made there. Au revoir Bain de Bretagne!