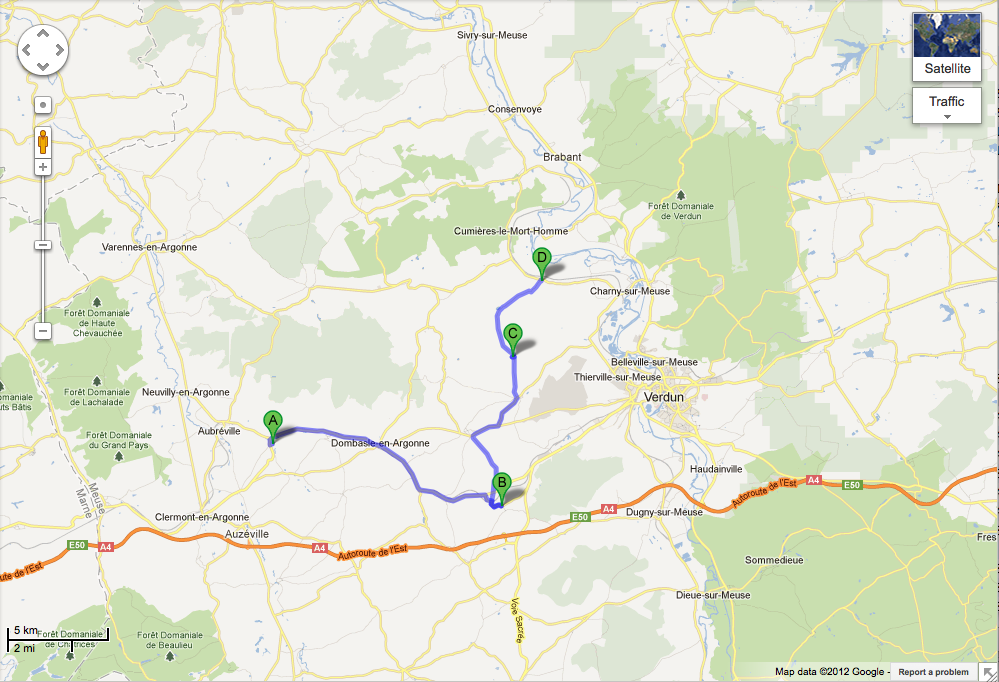

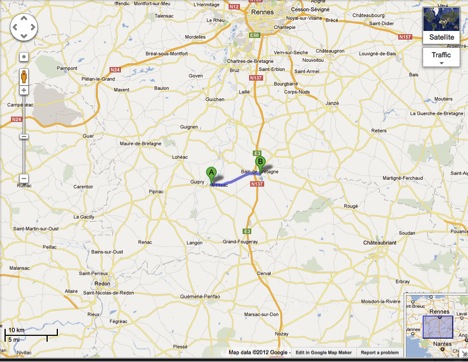

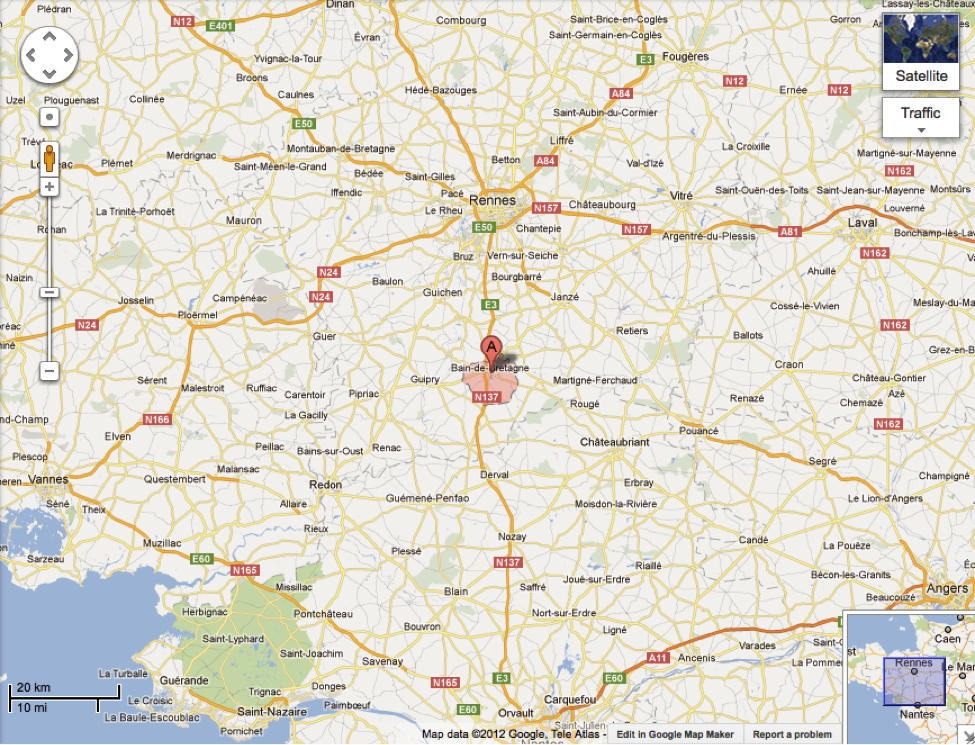

[CMC enlisted 1917-4-17] On typing paper

CMC Camp Sherman 1918 to 6-3

[Chilicothe, OH] 2.

[Pride is where artillery training took place, see CMC train from Camp Sherman–to 1918-6-11, p. 14]

on the hillside. I remember very distinctly of argufying with one of my comrades about those piles of brush. “Sook,” he says, “you can easily see them move. They are surely cattle.” But this was only a visual error as was later proven by closer view of the slope.

Pitched or rather nestled betwixt these two hills is the camp of which I had my first months of enlisted experience of military life. Tis true that I had been a student of military tactics at one of our early training camps, but when the time came for the distribution of commissions, I was in some manner neglected in the count. Those months of training proved so little fruitful for my efforts put forth that I shall refrain from mentioning them further in these pages, however I must not refrain from saying that I was very much disappointed and discouraged at the outcome of my attempt at being an officer, but later with more army experience my discouragement approached a minimum and now I really congratulate myself at my failure.

3.

On the East side of the camp flowed the Scioto River, with its ever winding run it finally flowed southward with is swelled the waters of the Ohio. To the north and south of the camp the river closed but near the center it widened so as to make a broad level valley for the erection of barracks for the housing of the soldiers, which were for the most part completed by October following the declaration of war. [from the comma, in pencil]

In the center of the camp ran the highway which was ever full with the stream of traffic which is necessary to care for forty thousand men. To stand by the side of this highway in the evening especially when the camp was being created and for awhile afterwards, one might think without due reflection what he was standing on the street corner of some great metropolis and watching the

4.

I have often wished as I sat on the banks of the old Indian river that I could roll back the waves of its book and read the pages of what it has seen with its own eyes. It could certainly tell some interesting stories if it could only speak what it has seen

It has seen the mound builders, of whom we know so little, build his monster and minute mounds. And too it could tell us all about these aboriginal inhabitants of this camp community with minute accuracy, something which to-day rebukes the lust [?} of Archeologists. For what did they use these little hlllocks of dirt for worship, for homes, for fortifications of the burial of the dead? Scientists have researched these communities and although they are able to find relics and skeletons of these primaeval [sic] inhabitants, they are speechless when it come to an accurate description of these prehistoric events. The river has all this in its memory.

Many are the occurrences of interest to an Ohio historian which

5.

have occurred in the little valley—in and about the town, Chillicothe which is located at the southern end of the camp.

Chillicothe, the oldest town of the State of Ohio will be to the Ohioan what the city of Rome is to the Italians—the one time metropolis and capital of Ohio. I can see with my mind’s eye those early Kentucky settlers crossing over the Ohio and proceeding northward until they could find a suitable place for settlement. Filled with the hopes of a freer life and of greater opportunity they must have been imbued with a spirit akin to a Aeneid or the spirit of the present day American Crusader who goes forth that he might make the world a more decent and respectable place in which to abide. Well too perhaps there was the spirit of fortune making driving these pioneers northward. But certainly these early possessors of these valleys fought some remarkable battles with the natives for the possession of the spot and its environs. In fact we

6.

can read about these promiscuous battles penned by an erudite man who must always accompany a group of men as an intelligent leader in their uncertain future success.

The river’s also recorded the fact that this locality was previously used by the Americans as a military camp. The story is told, and I will not vouch for its historicity, of the British plot which which [sic] hatched by some English prisoners stockaded here during the revolutionary war. These prisoners having been retained here for some time decided in the minds [?] of genius that they would make an escape. Escape they would if they must kill all the guards to do it. In fact the nature of the plot was to kill the guards and then escape. Thru the ingenuity of American secret service the plot was disclosed. The criminals were dealt with according to the degree of their crime. They were quietly taken out, four of them, I believe, and

7.

placed behind a large log. The log was great enough to hide all except their heads. Only these were necessary for the firing squad to practice in volley. The firing squad began the volley and all save one immediately succumbed. He instead immediately leaped and shrieked into the air with the wail of a most distressed creature. A second attempt by the sharpshooters effected the desired result and there the last man lay dead on the sod. The men were buried near the rivers brink, and perchance the river is gradually washing away the interred bones of these unfortunate Englishmen. Ah this true that this valley is not void of all that would give it the tinge of the historical Tower of London or the early battle grounds on English soil. We tend to deprecate things American and turn to Europe for all that is great because of antiquity. America should be proud that it does not possess some of the historical wonders of Europe, such as the entanglements of King successorship, the revolutions, the

8.

the slaughters, the intrigues caused by religion and King successorship. Why is it that we are prone to worship and admire a thing because it is old? A university degree from an old established center of learning is more precious than that from some of our late American colleges. You ask a young man of American what his college is. He will instantly reply Cambridge, Oxford, Harvard, etc., while the one from some of our smaller and less known institutions which do work of equal grade will answer, when asked in a very modest tone, the name of some small or young college. Nine times out of ten, the newer colleges and universities are better equipped and have better buildings and equal professors to the old established schools. In fact I should rather attend a university created in the late half century because the atmosphere about such an institution is more up-to-date. That institution is more or less free from custom and moss covered ideas, which more or less tend to hinder the progress of

9.

any institution. Such criticism is particularly applicable to certain European institutions, which tend to hold forever to the antiquity of its ways. Of course one must recognize an element of good in such a condition, and such a method is particularly beneficial to some universities, because of the economical aspect—they spend nothing for experiment but take the advantage of others explorations, their mistakes, successes and discoveries.

We should be more appreciative of our country, the history of our cities and towns. In a few thousand from now the different of old world antiquity from that of ours will fade into insignificance, and then too perhaps that peculiarity of our desire of admiration of a thing because of its oldness will functions in our national patriotism. Our country is successful now because it is free from so many of those deep seated and aged differences which exist now in and between some of our European countries. We should be thankful for it.

The old camp with its [unveiled? unrivaled?] historical background seemed to possess the military

10.

atmosphere! One could not have chosen a better spot to train our young spirited Ohioans and Western Pennsylvanians than Camp Sherman, Ohio because of its natural location and historicity, and too you may rest assured that the soldiers of the 19th century who were trained on these parade grounds imbibed some of the spirit of these surrounding hills and of the valley.

As I look back upon the days, weeks and yes months that I spent there I cannot help but be forgetful of many of the annoyances that occurred—and they were many—time after time and only think of the many good times we had there and also of the honest endeavors of the people of our homeland, who did most every thing possible to make out days pleasant in the camp.

It was a difficult matter to sever a young man away from his home connections and make a soldier out of him in one day, and figuratively speaking this was the demand made upon the American young manhood in the days

11.

of the draft. America was and is a peace loving nation and as has been said by many of our foremost statesmen she does not covet any possessions other than that which she possess. This is the doctrine that rang out from coast to coast and was spread abroad from the public platform and newspapers of our great republic, and who should be the most ardent listeners to such a fine sounding doctrine. Those (?) the young Americans, because naturally the burden of (?) fighting was for them to bear, should America declare war.

However, just as soon as the time of I did not raise my Boy to Be a Soldier changed to that of “America Here’s a Boy for you”, we were all ready for the most part to answer that call, and what we helped to do is know by every American citizen. So for a young man to be wrenched from his homelife and place din a military subject to military discipline and all that accompanies it was a very sudden shock. The entire mental attitude and makeup of the young Americans had

12.

to be transformed in a night so to speak. One did not know what to expect in a military life. The average American knew nothing of the drill and the fundamentals of tactics and therefore was hazarding a leap in to the great unknown. It should be added, however that he entered th? camp with a keen sense of his duty and with the idea that if he did not make the best of his training he would stand a poor chance to outwit the Boshe in a bayonet combat.

Those first days of training were monotonous was the most part to many and to a few they were enticing and interesting. The routine of it all and knuckling down to the discipline which is necessary for a successful army tended to make the work monotonous.

So much was written during the early days of our war about camp lift that it is not necessary for me to reiterate these experiences in much detail.

I was among the first to enter the camp. It was not then completed. Many of the buildings were in the process of the making. My first experience was in the first of

13

September 1917, and I could write at length about the origin and growth of the camp which is unessential, since the men, and their experiences and accomplishments [last two words inserted] is the crux of my theme.

To see those men come in from all sections of Ohio and Western Pennsylvania, one’s mind would revert back to the sheep in a pasture or the

Those men when they first came in! Their eyes and appearance told the story of their inward feeling, which was expressed in “Here I am, take me and do as you please with me.” These men all lined up in their different colored uniforms, ranging all the way from the common worka-day blue overalls to the finest clothes that money could buy, were to say the least a motley sight and indeed that very much unmilitary. That was to come later. This is the thing they were to have in the few weeks following.

These men were lined up by the adjutant of each regiment and so many were sent to each battery or company. Whether a man The branch of service which a drafted man entered was purely accidental. The enlisted man’s choice [?] had. Some respect was paid

14

[Does this actually follow or go with another doc?] To see these men lined up in single file and distributed reminded me of a famer who had a large great number of sheep and desired to distribute them in his several fields. Or such a condition might be compared with a victor distributing his spoils,–The Adjutant acting as the victor.

Thus distributions were made and whether a better way could be found I know not. However, it seems that better discretion could have been used in pearing [?] many of the men, with whom I later became acquainted.

To see the change in the effect of army life upon the personal appearance of some of these men was marvelous—I remember one chap who had the appearance of a professional pedestrian who gained his livelihood in a beggardly fashion. His clothes were dirty and torn. His hair was long and dirty and unshaven and with all this [?] combination he presented an unsightly appearance. To be forgetful of the day he entered the camp he had taken on an extra swig of booze and was not at all balanced in his step. After he received the attention of the supply sergeant he came out dressed like a soldier and at the end of a month he straightened up and I doubt if his body who had travelled with him on the road would have known him, if he should should he accosted in his new uniform. This man—at least while he was in the army, was benefitted by his training, whether he will continue to be a man after his discharge, I know not.

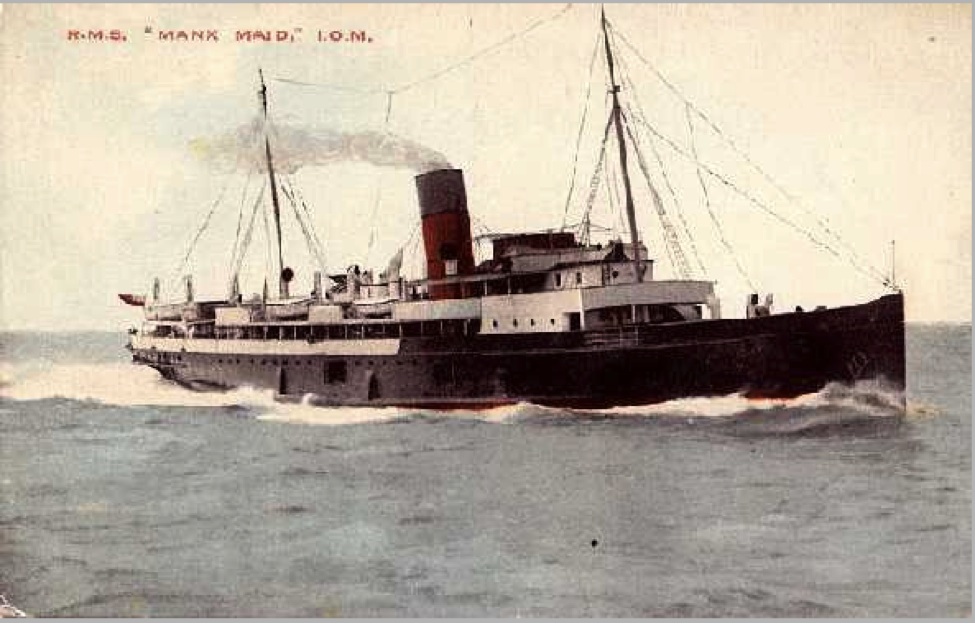

Those days in camp were not at all times monotonous. Indeed many pleasant remembrances linger in the minds of those who trained there. Those glorious anticipation days when we were to go home on a week end pass and get our feet under our Daddy’s table were pleasant to no little degree and when we we [were, obviously was intended] disappointed a glum ferle [?] of course possessed us. I remember one particular occasion that caused a glum feeling to reign in the camp midst. This occurred just a week or two before we were to embark for abroad. Passes had been issued to the allotted percentage which were to go home on a certain Saturday. This was practically their last chance, but what should happen but that all these passes were

[end of document]

http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=670

Camp Sherman

When the United States entered the First World War in April 1917, the nation was not fully prepared for the war effort. As a result, the government scrambled to create a system for training troops. Camp Sherman, located near Chillicothe, Ohio, was one of the new training camps. Ultimately, Camp Sherman became the third largest camp in the nation during the war. The camp was named after famous Ohioan and Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman. Construction began in July 1917, and the first recruits arrived in September. Before World War I ended, more than forty thousand soldiers had received training at Camp Sherman. The camp was eventually home to four different divisions: the 83rd, the 84th, the 95th, and the 96th. The war actually ended before the 95th and 96th were ready to go overseas.

The camp was built on top of Hopewell Indian mounds in the area. Some of these mounds had been destroyed by agriculture over time, but others were bulldozed to make way for the 1,370 buildings constructed at Camp Sherman. The camp was organized like a small city. In addition to barracks and offices used by the soldiers, there were theaters, a hospital, a library, a farm, and a German Prisoner of War camp. German POWs remained at Camp Sherman until September 1919, several months after the war had ended. There was also a railroad system, and the camp had its own utilities system.

Camp Sherman had a significant effect on nearby Chillicothe. It provided employment for many of the community’s residents and housed many soldiers’ families. Local businesses experienced significant increases in revenue because of the influx of population into the area. In addition, the people of Chillicothe tried to improve soldiers’ morale by offering entertainments and hosting soldiers for dinners at their homes.

In 1918, the influenza epidemic arrived at Camp Sherman. Thousands of soldiers contracted Spanish influenza in the late summer and early fall, and nearly twelve hundred died from the illness. Although the community of Chillicothe was quarantined to prevent the spread of the epidemic, some people outside of the camp still became ill and died of the disease.

When the war ended, the camp temporarily functioned as a trades school to educate veterans so that they were qualified for jobs. A hospital for veterans was also established. During the 1920s, the United States government closed Camp Sherman and ultimately dismantled it. Today, none of the original buildings still stand. The land originally occupied by Camp Sherman now has a number of uses. It is home to the Veterans Administration Medical Center, the Ross Correctional Institution, the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, a wildlife refuge, and the Chillicothe Correctional Institution.